A while ago I published a post describing our InnovateUK-funded research project investigating professional search strategies in the workplace. As you may recall, we surveyed a number of professions, and the one we analyzed first was (cue drum roll)… recruitment professionals.

It’s a profession that information retrieval researchers haven’t traditionally given much thought to (myself included), but it turns out that they routinely create and execute some of the most complex search queries of any profession, and deal with challenges that most IR researchers would recognize as wholly within their compass, e.g. query expansion, optimization, and results evaluation.

What follows is the second in a series of posts summarizing those results. In part 1, we focused on the research methodology and background to the study. Here, we focus on the search tasks that they perform, how they construct the search queries and the resources they use.

As usual, comments and feedback are welcome – particularly so from the recruitment community who are best placed to provide the insight needed to interpret and contextualize these findings.

4.2 Search tasks

In this section we focus on the search tasks performed by recruitment professionals. Evidently, candidate search is an important part of a recruiter’s work, but not exclusively so. Of the range of services offered by the organisations they represent (which were not mutually exclusive), candidate search (76%) and candidate selection (62%) were the most common (see Figure 3).

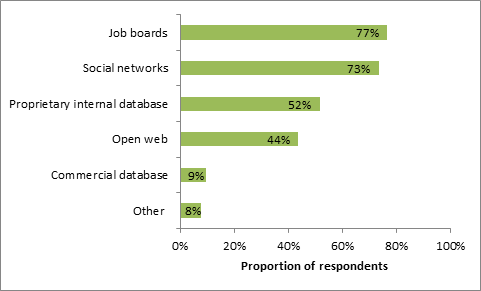

Job boards such as Monster, CareerBuilder and Indeed were the most commonly used resource that recruiters target when searching for candidates (77%), with a similar proportion (73%) also targeting social networks such as LinkedIn, Twitter and Facebook (see Figure 4).

We also examined the broader query lifecycle; in particular respondents’ usage of previous search queries and the degree to which they are prepared to share their work with others. 19% of respondents always used previous examples or templates to help them formulate their query, and a further 30% often did so (see Figure 5). In total, the majority of respondents (80%) used examples or templates at least sometimes, suggesting that the value embodied in such expressions is recognised by recruiters.

Most respondents (50%) said they were happy to share queries with colleagues in their workgroup and a further 22% were happy to share more broadly within their organisation. However, very few (5%) were prepared to share publicly, perhaps underlining the competitive nature of the industry (see Figure 6).

Table 1 shows the amount of time recruiters spend in completing the most frequently performed search task, the time spent formulating individual queries, and the average number of queries they use. As in Joho et al.’s survey [9], the variance is large so the measure of central tendency reported here is the median.

| Min | Median | Max | |

| Search task completion time (hours) | 0.06 | 3 | 30 |

| Query formulation time (mins) | 0.1 | 5 | 90 |

| Number of queries submitted | 1 | 5 | 50 |

Table 1: Search effort (queries submitted and time taken)

On average, it takes around 3 hours to complete a search task which consists of roughly 5 queries, with each query taking around 5 minutes to formulate. This suggests that recruitment follows a largely iterative paradigm, consisting of successive phases of candidate search followed by other activities such as candidate selection and evaluation. The task completion time is substantially longer than typical web search tasks [11].

4.3 Query formulation

In this section we examine the mechanics of the query formulation process, looking in detail at the use of a range of functions that recruiters believe are important in helping them complete their search tasks. To achieve this we asked respondents to indicate a level of agreement to statements such as “Boolean logic is important to formulate effective queries”, “Weighting is important to formulate effective queries (e.g. relevance ranking)”, and “I need to consider synonyms and related terms to formulate effective queries”. Responses were recorded using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strong disagreement (1) to strong agreement (5). The results are shown in Figure 7 as a weighted average across all responses.

The results suggest two observations. Firstly, the average of almost all features is above 3 (neutral) on the Likert scale. This suggests that recruiters are willing to adopt and leverage a wide range of search functionality to complete their task, which would be a marked contrast to the behaviour of typical Web searchers who rarely, if ever, use any advanced search functionality [12]. However, it could also reflect a degree of aspiration to simply try out such features, with no implication that they would ultimately offer any value on an ongoing basis.

Secondly, Boolean logic is shown to be the most important feature, with a weighted average of 4.25. This was closely followed by the use of synonyms (4.16) and query expansion (4.02). Although recruiters value this functionality, the support offered by current search tools is highly variable. On the one hand, support for Boolean expressions is provided by many of the popular job boards, and the challenge of creating and optimising Boolean expressions is the subject of a number of highly active social media forums (e.g. [7]). However, practical support for query formulation via synonym generation is much more limited, with most current systems relying instead on the expertise and judgement of the recruiter.

The lowest ranked feature, and the only one which scored below 3 on the Likert scale, was case sensitivity. This may be due to concerns that inappropriate use of case sensitivity may reduce recall, or it may be simply that automatic case folding is a default for most systems therefore manual intervention is relatively less important. Query translation was the second lowest, possibly because most respondents worked primarily in one language (i.e. English).

The most popular methods were either using a text editor (43%) or simply pen and paper (22%), see Figure 8. This suggests a disparity between the level of complexity in the task and the level of support offered by existing search tools. This is further underlined by the use of taxonomies, which was relatively low (6%), despite the fact that a number of suitable resources exist for HR and related domains (e.g. Human Resources Management Ontology).

So that’s it for this issue. Next time we’ll cover:

- Results evaluation: How recruiters assess and evaluate the results of their search tasks, and the challenges this entails

- Features of an ideal search engine: Their views on any other features and functions additional to those described above.

If you have comments or feedback, please share below!