And finally… here’s the third installment of my trilogy of posts on the information retrieval challenges of recruitment professionals. The background to this (in case you missed the previous two) is that a few months ago I published a post describing our InnovateUK-funded research project investigating professional search strategies in the workplace. As you may recall, we surveyed a number of professions, and the one we analyzed first was (cue drum roll)… recruitment professionals.

It’s a profession that information retrieval researchers haven’t traditionally given much thought to (myself included), but it turns out that they routinely create and execute some of the most complex search queries of any profession, and deal with challenges that most IR researchers would recognize as wholly within their compass, e.g. query expansion, optimization, and results evaluation.

What follows is the final post summarizing those results. In part 1, we focused on the research methodology and background to the study. In part 2, we discussed the search tasks that they perform, how they construct the search queries and the resources they use. Here, we focus on how recruiters assess and evaluate the results of their search, and their views on the features of an ideal search engine.

4.4 Results evaluation

In this section we examine the results evaluation process, looking in detail at the strategies that recruiters adopt and the criteria and features they find important in helping them complete their search tasks.

Table 2 shows the ideal number of results returned for the most frequently performed search task, the average number of results examined, and the average time taken to assess the relevance of a single result. As in Table 1, the variance is large so the measure of central tendency reported here is the median. The median time to assess relevance of a single result is 5 minutes and the ideal number of results is 33. However, the number of results examined per query is lower (30), which suggests that recruiters may be less concerned with recall (i.e. ensuring all relevant results are reviewed) and instead adopt more of a satisficing strategy, evaluating only as many results as are required to create a shortlist of suitable candidates.

| Min | Median | Max | |

| Ideal number of results | 1 | 33 | 1000 |

| Number of results examined per search query | 1 | 30 | 100000 |

| Time to assess relevance of a result (mins) | 1 | 5 | 50 |

Respondents were asked to indicate how frequently they use various criteria to narrow down results. Responses were recorded using a 5-point scale from never (1) to always (5). Figure 9 shows the results as a weighted average across these values. Job function was the most important (4.34), followed closely by location (4.29). These choices mirror some of the factors found to influence expert selection, such as topic of knowledge (job function), physical proximity (location), perspective (industry sector/career level), familiarity (previous contact with recruiter) and availability [6].

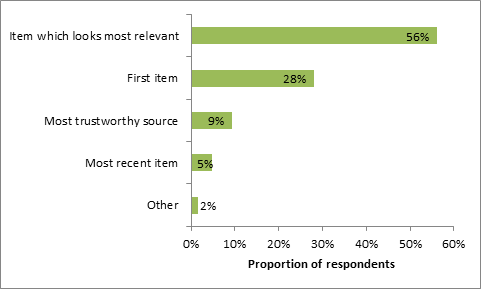

We also examined recruiters’ strategies for interacting with results sets. Figure 10 shows that the most popular approach by far was to start with the result that looked most relevant (56%). However, many others (28%) would simply click on the first result, implying a degree of trust in the ability of their particular search engine to rank candidates. This suggests that for these individuals at least, the weighting function referred to in Figure 7 may be of particular value. The number of respondents who targeted the most trustworthy source was relatively low (9%), implying a degree of ambivalence towards provenance. It also runs counter to the claim that “source quality is the most dominant factor in the selection of human information sources” [6].

When asked how they determined when their search task was complete, 50% of respondents said it was when they found a specific result, a further 38% said they it was when they couldn’t find any new relevant results, and 11% said it was when they had used all the allocated time for the task.

4.5 Features of an ideal search engine

In this section we examine other features related to search management, organisation and history that recruiters believe are important in helping them complete their search tasks. As before, we asked respondents to indicate a level of agreement to various statements and recorded the responses using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strong disagreement (1) to strong agreement (5). The results are shown in Figure 11 as a weighted average across all responses.

All features scored highly (above 3), with recency of retrieved results the most important (4.21). This reflects the need for recruiters to have confidence that the employment status and profile of the candidates they are selecting are up to date. The least important feature was exporting search queries (3.50), suggesting that the current workflow offers few opportunities for integrating them with other applications.

Concluding discussions

This paper describes the results of a survey of the information seeking behaviour of recruitment professionals. As such, it is the first study of its type, uncovering the search needs and habits of a previously unstudied community in a manner that allows direct comparison with other, well-studied professions, such as patent, medical and academic document search. It also presents a fresh perspective on the task of expertise retrieval, offering a new set of real world ‘people search’ scenarios.

Sourcing is shown to be something of a hybrid search task. In principle, the goal is to find individuals matching a specific brief, and in this respect it shares many of the characteristics of people search. In practice, however, the objects being retrieved are invariably documents (e.g. CVs and resumes) acting as proxies for the individuals concerned, so in this respect the workflow also shares characteristics of document search.

There are also important consequences for the IR community as a whole in particular regarding the assumptions underlying many of its research priorities. For example, the prevalent view of much academic IR research assumes that searches are formulated as natural language queries [13], but the findings of this study show that many professional searchers prefer to formulate their queries as Boolean expressions. The key findings of this study are as follows, with verbatim quotes from survey respondents shown in italics where applicable:

- Recruiters display a number of professional search characteristics that differentiate their behaviour from web search [14]. These include lengthy search sessions which may be suspended and resumed, different notions of relevance, different sources searched separately, and the use of specific domain knowledge: “The hardest part of creating a query is comprehending new information and developing a mental model of the ideal search result.”

- Recruitment professionals use some of the most complex queries of any community and actively cultivate skills in the formulation and optimisation of such expressions (to the extent that some are referred to as ‘Boolean Blackbelts’).

- Despite the structural sophistication of their queries, recruiters find the selection of suitable terms to be an ongoing, manual challenge: “The specific job is so new I cannot find terms used on resumes to match.”

- Recruiters’ search behaviour is characterised by satisficing strategies, in which the objective is to identify a sufficient number of qualified candidates in the shortest possible time: “Generally speaking, it’s a trade-off between time and quality of results. [If] I can’t identify the required information in the available time… this is because the data is not present in any of my go-to data sources, and working around that limitation isn’t the best use of the time.”

- The search tasks that recruiters perform are inherently interactive, requiring multiple iterations of query formulation and results evaluation.

- The average time spent evaluating a typical result is 5 minutes. This calls into question the findings of previous research, (e.g. [15]) in which it was claimed that the average duration was as little as 7 seconds. This discrepancy could be explained by the fact that self-reported responses may reflect a (possibly subconscious) desire by respondents to project a more diligent or painstaking approach to their work. However, it could also be an artefact of the methodology used in the previous study, in which eye tracking fixations were used as a proxy for task duration, even though dwell time alone may not accurately reflect the true cognitive boundaries of the evaluation task or account for repeated iterations of attention given to a particular document.

These findings motivate further research into the value of various types of search functionality used by recruiters and the broader task context within which that functionality must be integrated. The evidence suggests that the impact of IR research on search tools currently used by recruiters is modest at best and that their needs may be poorly supported by incumbent tool developers: “The problem does not lie with the algorithms; it lies with the assumptions made by developers that do not understand how head-hunters think.” It would appear that the progress being made in other, more consumer oriented search domains (particularly mobile search assistants such as Siri and Cortana) has yet to be fully reflected in the design of search tools for the professional recruiter.

Respondents to the survey described in this paper reported that they use complex Boolean queries heavily. However, this does not imply that such expressions are the ideal way to articulate recruitment information needs. Instead, it may reflect the fact that recruiters currently do not have anything better at their disposal, and Boolean queries are the only way in which to express their requirements in a transparent and repeatable manner.

In our discussions with recruiters some have suggested that the first query shown in Section 1 could be expressed more simply, more concisely and more readably in the form of attribute-value pairs, such as:

Role: Software Developer (+Related Terms = All);

Experience: Java, J2EE, Struts, Spring;

Skills: Computer Algorithms, Databases (+Related Terms = 1st degree);

General Skills: Problem Solving;

This formalism could then be automatically augmented by:

- Inclusion of domain-specific search criteria, driven by a recruitment ontology;

- Presentation of related terms for specific occupations, dynamically filtered according to the current query formulation;

- Support for expanding with synonyms and related terms;

- Support for truncations, wildcards, misspellings, etc.

This example assumes and perpetuates the role of queries as the prime expression of information need. However, a ‘search by example’ approach may offer a more promising alternative. Assuming that a number of exemplar candidates have already been identified, a recruiter may prefer automatic functionality to “Find people like this”. In this instance, the skill would be in configuring the similarity metrics to optimise their effect on the result set. Moreover, such configurations could themselves be saved and reused in the way that queries are currently.

However, such automated systems may not be the ideal solution for an industry as competitive as recruitment. Successful recruiters pride themselves on being able to “speak the language of search” and locate candidates that others cannot. Whilst a machine learning system may be able satisfy generic sourcing needs, it risks sacrificing transparency for ease of use, and may offer less value to recruiters who view their query formulation skills as a source of competitive advantage.

In conclusion, we would hope that these findings will inspire the creation of new IR test collections and evaluation tasks. There are those in the recruitment profession who share this ambition and call for an opportunity to compare and contrast search strategies in an open and publicly visible forum [16]. It is our belief that the IR community could contribute to this goal and in doing so facilitate the translation of IR research into positive impact on a global industry.